Rules

Illegal Pitches

Illegal Pitches

There are a large number of rules that apply only to the pitcher, and nearly all of them apply only when the pitcher is in contact with or astride the pitching plate (the "rubber"). When there are runners on base, these actions result in a balk. When there are no runners on base, most (but not all) of these actions result instead in an illegal pitch.

Pitching prohibitions

Illegal pitches and "pitching prohibitions" are covered in Rules 6.02(b) and 6.02(c)(1-9):

6.02(c)(1): First, the pitcher may not touch the ball after having touched his mouth or lips unless he first wipes his hand dry before touching the ball. This applies within the 18-foot circle surrounding the pitcher's plate (that is, while on the mound). Second, while in contact with the pitcher's plate, the pitcher must not even touch his mouth or lips.

- Exception: In cold weather, with agreement of both managers, you may allow pitchers to blow on their hands while on the mound.

- Penalty: Remove the ball from play and warn the pitcher. If the pitcher does it again, call an illegal pitch and award a ball to the batter.

6.02(c)(2): Pitcher may not spit ("expectorate") on the ball, either hand, or the glove. The umpire has some discretion in judging intent, so that he may issue a warning instead of ejection on the first violation.

6.02(c)(3): Pitcher may not rub the ball on his glove, clothing, or on himself. He may only rub the ball with his bare hands.The umpire has some discretion in judging intent, so that he may issue a warning instead of ejection on the first violation.

6.02(c)(4): Pitcher may not apply any foreign substance to the ball. This goes beyond the "expectorate" prohibition and applies to anything at all (including dirt).

6.02(c)(5): Pitcher may not deface the ball (cut, scratch, or in any way alter the natural state of the baseball).

6.02(c)(6): Pitcher may not deliver a ball that's been altered in any way. This covers the scenario where the catcher or other member of the team alters the ball. If a ball is badly scuffed due to normal wear and tear, the pitcher may request a new ball from the umpire.

6.02(c)(7): The pitcher may not have on his person any foreign substance. Just having posession on the field of an illegal substance is sufficient to draw a penalty. (Rulebook comment: "The pitcher may not attach anything to either hand, any finger or either wrist (e.g., Band-Aid, tape, Super Glue, bracelet, etc.). The umpire shall determine if such attachment is indeed a foreign substance for the purpose of Rule 6.02(c)(7), but in no case may the pitcher be allowed to pitch with such attachment to his hand, finger or wrist.")

6.02(c)(8): The pitcher may not intentionally delay the game by throwing the ball to players other than the catcher while the batter is in the box and ready to bat, except when this is a legitimate attempt to retire a runner on base. Warn the pitcher, and if it continues, you may eject the pitcher.

6.02(c)(9): The pitcher may not intentionally pitch at the batter. If you suspect the pitcher of intentionally throwing at a batter, you may warn the pitcher, or eject, if warranted. You may also, if appropriate, eject the team manager. You may also apply an "official warning" to both benches, such that subsequent instances will result in ejections of pitchers from either team.

Penalty for an illegal pitch

The pitch shall be called a ball. If a play follows the illegal pitch the manager of the offense may advise the plate umpire of a decision to decline the illegal pitch penalty and accept the play. Such election shall be made immediately at the end of the play. However, if the batter hits the ball and reaches first base safely, and if all base runners advance at least one base on the action resulting from the batted ball, the play proceeds without reference to the illegal pitch.

Important: Even if the team elects to take the play, you still recognize the infraction and appropriate penalties should be applied.

NOTE: A batter hit by a pitch shall be awarded first base without reference to the illegal pitch.

- Details

- Hits: 60167

Legal Pitching Positions

Legal Pitching Positions

There are two legal pitching positions – the windup position [ 5.07(a)(1) ] and the set position [ 5.07(a)(2) ]. What differentiates the two is the position of the pitcher's feet as he engages the pitching rubber prior to delivering the pitch.

Important: The terms "pivot foot" and "free foot" are important. The pivot foot corresponds to a pitcher's handedness. That is, a right-handed pitcher's pivot foot is his right foot; for lefties, the pivot foot is the left foot.

In this article we're covering three topics:

The Windup Position

Pitchers typically use the windup position when there are no runners on base, or, if there are base runners, when there is little or no threat the runners will steal (e.g., R3 only or bases loaded). This is for two reasons.

First, the windup position imposes limits on the legal actions the pitcher may take which make it difficult to hold runners on their bases. Second, the pitching motion to the plate takes longer than from the set position, which would give a base runner an advantage when stealing. So the windup position is a handicap with runners on base.

The windup position puts specific requirements on the pitcher by rule:

- The pitcher must stand facing the batter and his pivot foot must be touching the pitching rubber. (More about foot positions below.)

- Before delivering the pitch, he will bring both hands together in front of his body. Once brought together, the pitcher may not separate his hands except to do one of three things:

- Deliver the pitch to the batter,

- Step and throw to an occupied base to pick off a batter, or

- Properly disengage the rubber by stepping backward off the rubber with the pivot foot.

- If the pitcher separates his hands other than for these three reasons, it is a balk.

- From the windup position, any natural movement associated with delivering the ball commits the pitcher to pitching the ball in a single, continuous motion. This includes any motion by hand, arm, or legs. Failing to deliver the pitch is a balk (with runners on base).

The feet in the windup position

In the windup position, the pitcher must stand facing home plate with his pivot foot in contact with the rubber while his free foot is on or behind a line extending through the front edge of the pitching rubber. Both feet must be facing home plate.

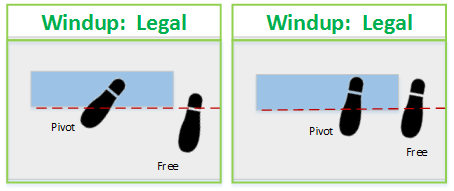

The images below the show two arrangements of the pitcher's feet in the windup position, both of them perfectly legal. The red dotted line represents the front of the pitching rubber.

Figure 1. Legal windup position

In both examples, the pivot foot is in contact with the rubber. That's a requirement. The free foot can be beside the rubber, but not in front of it. Some portion of the free foot must be touching or behind the red line marking the front of the pitching rubber.

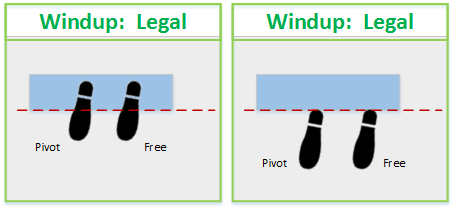

Following are two more examples of the feet in the windup position. The image on the left depicts the classic setup. The image on the right is also legal, and is perhaps the most common arrangement that you'll see, with both feet in front of the rubber and just touching it.

Figure 2. Legal windup position

On the frequently imperfect ball fields that amateurs play on, the condition of the pitcher's mound is often quite poor, usually with a deep hole in front of the rubber. The one shown here is worse than most, but you get the idea.

On these fields, the only way a pitcher can adopt the windup position is to set up in the hole in front of the rubber. There should be no daylight between the back of the foot and the front of the rubber, but sometimes there will be a sliver of light. Just let it go. The setup is legal.

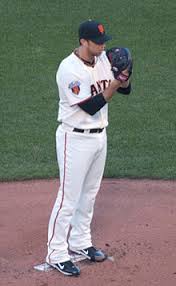

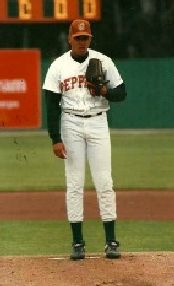

Look at the two photos below. Notice the position of the feet. These two photos depict examples of the legal windup positions. The photo on the right show the pitcher taking signs from the catcher; in a moment, he will bring his hands together (as you see on the left) before delivering the pitch.

In the photo below, the pitcher is just starting his windup from the windup position.

Important: It's important that you glance at the pitcher's feet on every pitch as he engages the rubber and that you make a mental note of the pitching position – windup or set. His pitching position affects what he is allowed to do and what actions may result in a balk or illegal pitch.

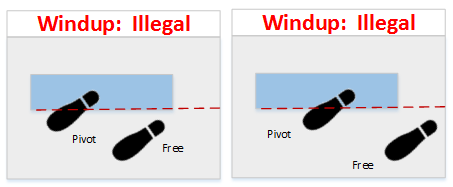

Now let's look at arrangements of feet that are not legal for the windup position. Again, it's all about the feet and the red line.

Figure 3. Illegal foot positions from the windup

In both illustrations, the pivot foot is correctly positioned in contact with the rubber. However, in both cases the free foot is entirely in front of the rubber and not in contact with it. In the example on the right, it doesn't matter that the free foot is off to the side of the rubber. What makes the position illegal is that the free foot is beyond the front of the rubber. The feet should also be pointed more toward home plate.

Pitching from the windup position

A pitch from the windup position begins with an initial step with the free foot either to the side or back of the rubber. Either motion is allowed. What's important, though, it that once the motion begins, it must be completed in a single continuous motion. The pitcher cannot hesitate or stop. If he has runners on base, he cannot throw to a base once he's started his pitching motion. He must deliver the pitch, or it is a balk.

Here's a five-second video demonstrating a pitch from the windup position.

The Set Position (and the stretch)

Pitcher's typically switch to the set position when there are runners on base and there is a threat to steal. This is because the set position gives the pitcher more options for containing base runners. That said, increasingly pitchers are using the set position in non-steal situations as well because it provides a simpler, more compact motion. This is particularly true in youth leagues.

The set position is also called the stretch. This is not technically correct, but has nevertheless become common usage. Actually, "the stretch" is a movement that a pitcher makes when pitching from the set position; it's that motion when the pitcher leans in to take signs from the catcher prior to straightening up and coming fully set. We'll see this in a moment.

The feet in the set position

In the set position [ 5.07(a)(2) ], the pivot foot is on or in front of the pitching rubber and fully in contact with it. The free foot is beside the pivot foot on the home-plate side. Rather than facing home plate (as with the windup position), the pitcher is facing the general direction of third base (if right-handed) or first base (if left-handed).

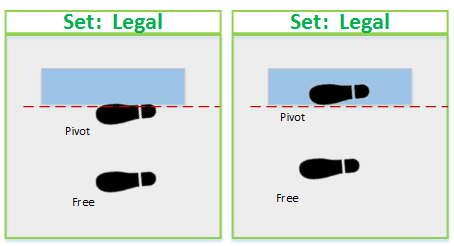

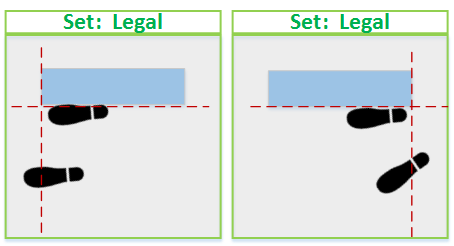

Figure 4. Two views of legal foot positions in the set

There are three critical points in determining the legal foot positions in the set:

- The pivot foot is on or touching the rubber,

- The pivot is entirely inside the left and right edges of the pitching rubber, and

- The free foot is entirely in front of the pitching rubber.

Following are two photos of pitchers in a legal set position. The photo on the left shows a left-handed pitcher and shows how the set position helps hold a runner on base. In both photos, though, you see the pivot foot touching and parallel to the rubber and the free foot entirely in front of it.

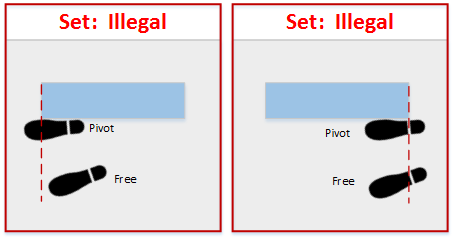

What makes the feet illegal in the set position is when the pivot foot is outside the pitching rubber – either to the left or to the right of the red line marking the edges of the rubber. You can see this in the illustrations below. Note that in the image on the right, the free foot is also outside the edge of the rubber, but that is not the problem. The position of the pivot foot, not the free foot, is what makes the position illegal.

Figure 5. Illegal foot positions in the set

Pitching from the set position

First, let's repeat one very important point that we covered in our article, The Pitcher. When the pitcher has his pivot foot engaged (touching) the pitching rubber, he is, by rule, a pitcher; when his feet are not engaged to the rubber, he is simply another of nine fielders.

This is important, because the special rules for pitchers only apply while he is engaged to the rubber (when he is "technically" a pitcher). When the pitcher disengages, these restrictions no longer apply.

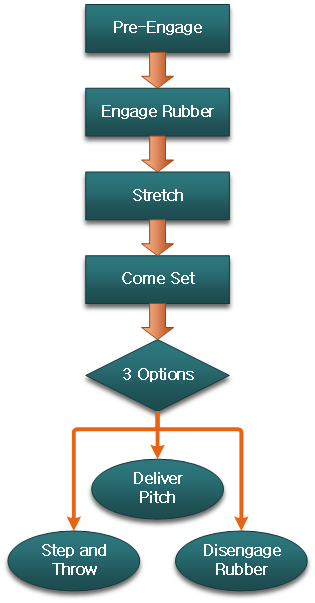

There are five stages to pitching from the set position. Let's assume for now that there are runners on base.

Pre-engage. Young pitchers are taught to engage the rubber by first straddling it. In this position, because they have not yet engaged the rubber, they are technically still fielders so they can quick-throw to a base from this position without penalty. Here's typical foot positions during pre-engage.

Pre-engage. Young pitchers are taught to engage the rubber by first straddling it. In this position, because they have not yet engaged the rubber, they are technically still fielders so they can quick-throw to a base from this position without penalty. Here's typical foot positions during pre-engage.

- Engage the rubber ("toe the rubber"). Then the pitcher engages the rubber by moving his pivot foot to its proper position on or in front of (but touching) the rubber, and adjusting his free foot in front of it, as shown in the Figure 4. The player is now technically a pitcher, so he is limited in what he can do. He can continue with the pitching sequence, step and throw to a base, or he can disengage the rubber, becoming a fielder once again, and then start the sequence all over.

Important: Pitchers must have possession of the ball when they engage or straddle the rubber. If they don't, you have a balk. Pitchers are normally taught to keep the ball in their hand, but having it in the glove is allowed. If the ball is in their hand, it must be at their side or behind them, as you see in the photos below.

- Go into the stretch. The next step is taking signs from the catcher. From the set position, the pitcher typically takes signs by going into the stretch. That is, he moves his free foot forward and leans in toward home plate. However, this is not required. Some pitchers take their signs from the position they acquired when they toed the rubber. This is allowed. Here are two views of the stretch, one by a righty, the other a lefty. You can see there is quite a bit of variation from pitcher to pitcher.

- Come set. After taking signs, the pitcher comes set by drawing himself upright and bringing his hands together with the ball. The pitcher in the photo below has come set with his hands at his chest. Some pitchers come set with their hands lower, near their belt, while others have their glove up in front of their face.

Once the pitcher comes set, a new set of restrictions apply:

- He can no longer turn to look at runners on base. He can turn his head but cannot turn his shoulders or body. If he does, it's a balk.

- He cannot change the position of his hands in the set, neither up nor down. Doing so is a "double-set" and it's a balk.

- Once he brings his hands together, he cannot separate them – except to complete one of the three actions we discuss in the next stage (deliver the pitch, step and throw to a base, or disengage the rubber). Separating the hands without completing one of these actions is a balk.

- He must come to a complete and discernible stop in the set position before delivering the pitch. The most common balk call for young pitchers is "blowing through the stop." Pitchers will bring their hands together and move continuously into their delivery without pausing. This is a balk.

- Finish the sequence in one of three ways:

- Deliver the pitch. Following the discernible pause, the pitcher may deliver the pitch to the batter.

- Step and throw to an occupied base. The pitcher may step and throw to an occupied base for the purpose of picking off a runner. However, in doing so he must meet certain requirements. He must step in the direction of the base, and his step must gain distance in that direction. The hallmarks of a legal step-and-throw is the lead foot gaining distance and direction. A jump step is also legal, but, again, the lead foot must gain some distance in the direction of the base to which the throw is made.

- Properly disengage the rubber. The pitcher may disengage the rubber, but must do so properly. He must step backward off the rubber with his pivot foot. Improperly disengaging the rubber is a balk. However, once he has disengaged the rubber, he is now a fielder, not a pitcher, and all of the restrictions placed on the pitcher are no longer in effect.

Here's a flow chart depicting the pitching sequence from the set position.

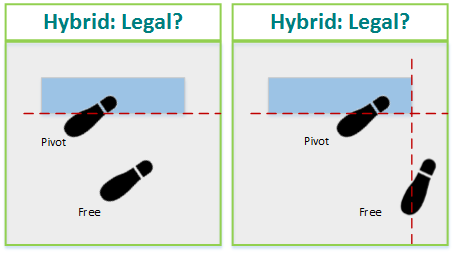

The Hybrid Position

In recent years, a so-called "hybrid" position has gained currency in some quarters. The position is controversial, however, because it does not, strictly speaking, meet the requirements for either the windup or the set position. Despite this, the hybrid position is being allowed in the major leagues and is being seen increasingly in NCAA games.

The high school federation (NFHS), however, is not allowing the hybrid position and in recent years has made it a point of emphasis to call a balk (with runners on base) or an illegal pitch when a pitch is delivered from the hybrid position.

Because the situation is fluid, we can't provide clear guidance on handling the hybrid setup. For guidance, discuss this with your association.

Here's a look at the hybrid setup. The issue is not with the free foot's position; rather, the problem is with the position of the pivot foot – it is engaged to the rubber, but is not entirely in contact with the rubber, nor is it parallel to the rubber.

Here is a photo of former Yankees great, Mariano Rivera; he has engaged the rubber in the hybrid position. His feet do not meet the technical requirements for either the windup or the set position.

- Details

- Hits: 210289

The Pitcher

The Pitcher

Of the triad at the core of baseball (batting, fielding, and pitching), pitching is far and away the most complex. This is true not just for players and coaches, but for umpires as well. There are a lot of rules governing pitchers and pitching, and many of them are nuanced.

Aspects of umpiring like working the plate, calling balls and strikes, and particularly seeing and calling balks, take time and experience. Even a seemingly silly question like "When is a pitcher not a pitcher?" is actually an important and meaningful question.

In fact, umpiring pitchers and pitching is so broad a topic that we cover it over five articles. The present article, The Pitcher, is first in the series. The remaining four are:

What is a pitcher?

That sounds like a stupid question, but it's not. To get at the answer, let's start with the rule book: Definitions (pitcher): "… the fielder designated to deliver the pitch to the batter."

Simple enough. But there's more to it. The player designated in the lineup "to deliver the pitch to the batter" is only a pitcher (technically) when he is in contact with the pitching plate. When that player is not in contact with the pitching plate (the "rubber"), the player is no longer (technically) a pitcher, but rather just a defensive fielder.

So to recap, the pitcher is the player designated on the lineup to deliver the pitch; but then we learn that he's only really a pitcher when in contact with the pitching rubber, and that at all other times on defense, he's simply another fielder. What gives?

What gives is that there are several pitching rules and prohibitions that apply to the pitcher when (and only when) he is in contact with the rubber. When he is not in contact with the rubber, he's simply a defensive fielder and those pitching rules no longer apply. For example, while not engaged (that is, while he's a fielder), the player can fake a throw to any base. When engaged to the rubber, however (when he's a pitcher), faking a throw to a base is almost always a balk.

The matter of what a pitcher can and cannot do depends on two things. First, as we've said, it matters whether the "pitcher" is a pitcher or a fielder – that is, whether he is in contact with the rubber or not. Second, the pitching rules vary depending on whether the pitcher is in the windup position or the set position. And finally, which rules apply depend also on the point in the pitching sequence the pitcher has reached.

We go into detail on the pitching positions, the pitching regulations with respect to the pitching positions, and then about balks and illegal pitches in the two companion articles, The Pitching Positions and Balks & Illegal Pitches.

- Details

- Hits: 34282

Obstruction

Obstruction

In our discussion of interference, we said that the opposite of interference is Obstruction. That is, while interference penalizes base runners for impeding fielders who are making a defensive play, obstruction penalizes fielders who impede base runners.

Here's the rule-book definition, found in Definitions (obstruction):

Obstruction is the act of a fielder who, while not in possession of the ball and not in the act of fielding the ball, impedes the progress of any runner.

Note the emphasis on the words "while not in possession of the ball and not in the act of fielding the ball." This is very important and is something we'll come back to. Another important point is that there does not need to be physical contact to have obstruction.

Beyond the rule-book definition, Rules 6.01(h)(1) and 6.01(h)(2) extend the definition and explain the two types of obstruction, commonly called Type 1 obstruction and Type 2 obstruction (for their treatment in Rules 6.01(h)(1) and 6.01(h)(2), respectively).

Note: The 2014 revision to the Official Baseball Rules, in renumbering the rules, has disposed of the time-honored Type A and Type B obstruction. In the new rule book, these are now. Type 1 and Type 2, respectively.

Type 1 (type A) Obstruction: Happens when a base runner is impeded while a play is being made on him. For example, if a catcher without possession of the ball blocks the plate, preventing a runner from having unimpeded access to the plate, this is obstruction. This is an immediate dead ball and bases are awarded as appropriate.

Type 2 (type B) Obstruction: Happens when a base runner is impeded when there is not a play being made on the runner. For example, when F3 is standing on first base watching a base hit to the gap and the batter-runner collides with him while rounding first, that obstruction. However, because the ball is in the outfield and no play is being made on the runner, this is a delayed dead ball. You make a signal but you let play continue and then deal with penalties (if any) after play has concluded.

Important: High school rules (NFHS Baseball Rules Book) treat obstruction differently from OBR. In NFHS, obstruction is always a delayed dead ball (never immediate dead ball). On conclusion of action, kill the ball and award bases to nullify obstruction, but always award a minimum of one base beyond the point of the obstruction. See NFHS Rules 2-22-1 and 8-3-2.

Now let's go deep on OBR Types 1 and 2 obstruction.

Type 1 obstruction

As we've said, Type 1 obstruction occurs when there is a play being made on the runner at the time the obstruction occurs. Call time immediately and award bases. We'll discuss base awards in a moment. Here are a couple of examples of Type 1 obstruction:

Catcher blocks the plate

A base runner has rounded third, heading for home, and the catcher is three feet up the line, blocking the base path, calling for the ball. The ball is in flight but before the catcher receives the ball the runner is forced to slow down and deviate from his normal path to avoid a collision. Just as the runner passes by (or slides by) him, the catcher receives the ball and applies the tag.

Do we have an out? Not on your life. The umpire calls "Time. That's obstruction! You (pointing to the runner), home." The runner is safe and the run scores. (But make sure the runner touches home plate. He can be put out on appeal if he fails to touch the plate.)

We're talking about the catcher setting up in a blocking position without possession of the ball. You must watch the catcher before the play arrives, while the play is still developing, and you must be aware of where the ball is. This will prepare you to see and call the obstruction if it occurs.

Important: One of the most difficult calls you'll ever make is when the catcher is in a legal position, but, as the runner arrives (at full speed), a bad throw pulls the catcher into the runner's path. Here you have a collision (literally) of two rules - obstruction and interference. The interference rule tells us that a fielder has the right to make a play on the ball, and yet the obstruction rule tells us that the runner has the a right to the base path.

We're in the territory of what's commonly called a "train wreck," and there is no simple answer on how best to judge this. The most common umpiring advice supports a no-call, if you judge that both players were acting appropriately. Any action on the part of either player (either the fielder moves unnecessarily to impede the runner, or the runner deviates purposely to disrupt the fielder), and take that as a cue to call either interference or obstruction. But you need to be mentally ready because this one happens fast, so again, watch the players while the play is developing.

Fielder blocks the bag

You have a runner on first (R1). It's a close game so the first baseman (F3) is holding the runner on; the pitcher throws over frequently for the pickoff, but R1 gets back each time. Finally, with R1 leading off even more, the pitcher throws to first and R1 dives back reaching for the bag but instead his hand hits F3's foot and is stopped just short of the bag. Tag is applied.

Do we have an out? You guessed it – no way. "Time. That's obstruction! You (pointing to the runner), second base." The fielder must allow a clear, unimpeded path to the base. Blocking a portion of the bag with a foot is obstruction.

You can change up this scenario in a dozens of ways, move it to any base, and you get the same result. The point is, a fielder without possession of the ball cannot deny access to a base to a runner advancing or retreating.

Obstruction in a run-down

A run-down ("pickle") can be tricky because each time the fielders exchange the ball and the runner reverses direction, the runner has created a new base path. This is relevant because each time this happens, the fielder who just threw the ball is now probably in the runner's way, but is no longer in possession of the ball. That fielder, then, is in jeopardy of committing obstruction. You have to watch for this because it's easy to miss in the midst of a helter-skelter pickle, so (again) you have to be mentally prepared and watch the fielders (not just the runner) as the pickle develops.

We have more about this in our article, Basepath & Running Lane.

One wrinkle: "possession" vs. "imminent"

We've emphasized that a critical element of judging Type 1 obstruction is the fielder's having (or not having) possession of the ball. This begs the question: precisely what constitutes possession? Is it ball-in-glove? Or is it "imminent," that is, the ball is just arriving at the glove?

Once a player has possession of the ball, he can place himself between the runner and the base to which the runner is advancing (in fact, that's what he should do). But here's the problem: the professional rules (OBR) recognize a defensive player's right to occupy a blocking position when he is in the act of receiving the ball, when possession is "imminent." Many amateur leagues also recognize "imminent possession." Even Little League, until only a few years back (they changed in 2012, if I recall correctly) recognized imminent possession.

The problem with imminent is that one person's immanent is another person's obstruction. And therein lies a wedge of ambiguity that creates a potential for collisions (and serious injury) as the base runner hurries to beat the throw while the defender takes a wishfully blocking position in hopes of receiving the throw "imminently." Bang! It's a nearly impossible judgment call and a guaranteed argument (from one manager or the other, depending on how you call it).

Again, Little League has done away with imminent. So has the high school (NFSH) rule book, which now requires possession, as do a great many other youth programs. If you work leagues where this is not spelled out, then clarify at the plate meeting. For what it's worth, at my plate meetings I always specify that we're playing "possession," then wait to see if either manager disagrees or argues. If not, that's the rule.

And one last quirk

Rule 6.01(a)(10) Comment tells us that on a batted ball to the vicinity of home plate (a bunt, for example, or a dribbler on the first base line) if the the catcher and the batter-runner "have contact," there is normally no violation – no Type 1 obstruction. We're talking about incidental contact here, not something blatant. If you see either the runner or the fielder initiate an intentional act coincident with the contact, then make the call (interference or obstruction, depending on who initiated the contact).

Calling and penalizing Type 1 obstruction

Type 1 obstruction is a dead-ball infraction. This means, the moment you see it, call it: "Time! That's obstruction. You ... " and point to the runner and vocalize the base award "... you, second base" "... you, third base" or whatever the award calls for.

The penalty for Type 1 obstruction is awarding the obstructed runner one base beyond the base last legally touched. In the case of runners who are advancing, this means you award the base to which they were advancing. In the case of a runner obstructed while retreating (as in a pick-off attempt), award the runner the base beyond the one they were retreating to (and previously occupied).

Type 2 obstruction

In Type 2 obstruction, a fielder impedes the progress of a runner, but this takes place away from the action and away from the ball. That is, no play is being made on the obstructed runner. Instead, a fielder simply gets in the way of a base runner and causes the runner to fall, slow down, collide, swerve out of the way – anything that impedes the runner's progress.

Here are some examples of Type 2 obstruction. I'm sure you'll recognize most of these. But keep in mind that this is only a small sample of many situations that are Type 2 obstruction.

- Here's the classic (you see this one all the time in youth baseball). Big hit to the outfield through the gap. Batter-runner figures on a double. But the first baseman is standing on the bag (or near it) watching the ball – just standing there gawking, right in the runner's path. The runner either slows down and scoots around the first baseman, or he collides, maybe falling down. In any event, there are one of three outcomes for the runner. He either abandons his attempt to get to second, or he tries for second and makes it safely, or he tries for second and gets thrown out.

That's Type 2 obstruction, so you verbalize and signal the obstruction, but wait until action is complete before you call time and enforce the penalty – if at all. We'll go over this in the section on the penalty for Type 2 obstruction.

- Here's one that you saw in game 3 of the the 2013 World Series, where Boston third baseman Will Middlebrooks fell flat on his face but whose raised legs tripped Allen Craig, who was trying to score from third base. Umpire Jim Joyce called obstruction (Type 2) and awarded Craig home. The press made this out to be a controversial call, but in fact this is textbook obstruction. Here's a video of the play. You can see Joyce (he's U3) signalling the obstruction right away (left arm outstretched with a fist); and then, once Craig scores, the plate umpire is pointing back to the call at third. (The announcer incorrectly calls it interference, a mistake that we hear from announcers all the time.)

- Here's one that a lot of people don't know about. A fake tag (pretending that you have the ball and are making a play on the runner) – well, that's obstruction. Say you are a fielder and a runner is approaching second but you slap you glove like you've received the ball and so the runner quickly reverses direction to head back to first. That's obstruction. In another scenario, a runner is sliding into a base and the fielder (without the ball) lays down a tag, causing the runner to believe he's been put out. The runner gets up and starts trotting back to the dugout, whereupon the defense tags him out. That's obstruction. Nullify the out and return the runner to the base he would have achieved.

The penalty for Type 2 obstruction

Applying the penalty for Type 2 obstruction requires umpire judgment. In fact there is no prescribed penalty other than, once action has stopped (remember, this is a delayed dead ball infraction), the umpire shall call "Time" and shall "... impose such penalties, if any, as in his judgment will nullify the act of obstruction."

The emphasis on "if any" is important. It reinforces that in some cases (when, in your judgment, the obstruction is incidental and does not affect the progress of the runner) no penalty is necessary. On the other hand, you can, in your judgment, determine that the base award should be one base, two bases, or (theoretically) three bases. It's hard to imagine circumstances for a three-base award, but ... well, it's entirely in the hands of the umpire.

Mechanic for calling Type 2 obstruction

Unlike Type 1 obstruction, Type 2 obstruction is a delayed dead ball. This is important. When you see Type 2 obstruction, you verbalize it ("That's obstruction") and you point in the direction of the infraction, and as you do this you make a fist on your left hand, holding that arm out straight. But you let play continue.

When action on the play concludes, you act on the obstruction call by doing one of the following:

- If the result of the play is such that, in your judgment, the obstruction caused the runner to be put out or to not reach the base that he would have reached had the obstruction not occurred, then you call "Time" announce the infraction, then place the runner where, in your judgement, he belongs. Other runners advance if forced.

- If, on the other hand, the obstruction did not affect the play by causing the runner to be put out or to fail to reach base, then simply ignore the obstruction, say nothing, and move on. Often a base coach or player will have heard you verbalize "that's obstruction" and will ask you, then, why you're not enforcing a penalty. Call "Time" and explain (in three seconds or less) why you're not doing so.

Summary Table

| Type 1 Obstruction | Type 2 Obstruction | |

|---|---|---|

| Occurs when | Play is being made on obstructed runner | Play is not being made on obstructed runner |

| Action | Immediate dead ball | Delayed dead ball |

| Penalty | At least one base beyond the last base touched | Umpire judgment: place runner to nullify effect of the obstruction; this could be no award at all |

- Details

- Hits: 228896